On Balance

(Essay in progress)

Before the holidays, I got Covid, and now, four months on, I am still in poor health. Depending on who you consult, my body is recovering from its war with the virus, or the virus remains in my body, defanged, yet guerrilla, and my defenses are cluster bombing the forests. As a result, I have persistent lethargy that cycles intensity in unpredictable weeklong swings. Most of the time, my eyelids feel heavy, creaking in their hinges by my temples. In a down phase, my whole body feels subject to a new and denser gravity, pulling me groundward. During these ebbs, I’m so depleted that it’s painful to be out of bed.

Resilience, usually a hallmark of my operating style, has become precious and sensitive to crash in my fragile state. Any novel operation—negotiating apartment repairs with an uncooperative landlord; a disregulated or oppositional student; the grocery store parking lot—can cause my heartbeat to accelerate perceptibly and my body to thrum with an achy vibration that tells me, no matter where I am, that I need to get under covers and watch Youtube until I can calm all the way down. ||

Even if I chill on the weekends and take things slow, the low drumbeat of a five day work week inevitably sinks me. I avoid unnecessary mental, physical or emotional exertions, but many exertions are unavoidable. Groceries. Laundry. All relationships require some effort and thought to navigate skillfully, and I’ve purposely built a life that maintains dozens of them. Each, no matter how sustaining emotionally, is now also quietly depleting. My frailty becomes unavoidably self-reinforcing as I subtract the energy I’ll need today from what I know I’ll have and, forseeing myself in the red, become anxious in anticipation.

Worryingly, I’ve also begun experiencing unaccountable testicular pain, dull and achy, possibly stress induced.

Meanwhile, a new travail has entered my life: floating my illness through the mired swamplands of Kaiser Permanente’s overburdened medical bureaucracy, where the solid land of a doctor’s attention is scarce and brief. The earliest appointment I could get with a urologist is in three weeks, and the Imagining Department declined to schedule the testicular ultrasound my GP ordered until after the urology appointment, leaving me marooned with my imagination, unless I want to spend all day at the ER. I’m resistant to hypochondria, but that doesn’t make me immune to testicular cancer. Thump thump thump thump five battery points disappear with that thought.

As a proactive alternative to clinical care, I’ve been consulting my mom, the Internet, my Chinese-aunty/barber Joyce, my girlfriend, my girlfriend’s acupuncturist, an out-of-network support group of medically-trained friends, and clinicaltrials.org.

This last one is a dating service where those who have reached the limits of conventional Western medicine yet remain symptomatic can match with researchers trying to expand those bounds. My doctor friend Matty predicted that Kaiser would do nothing further than to tell me to rest until I get better, since long Covid (post-acute sequelae of covid-19, or PASC) is a cutting-edge syndrome, but that I may be able to enroll in a clinical trial for more tailored care.

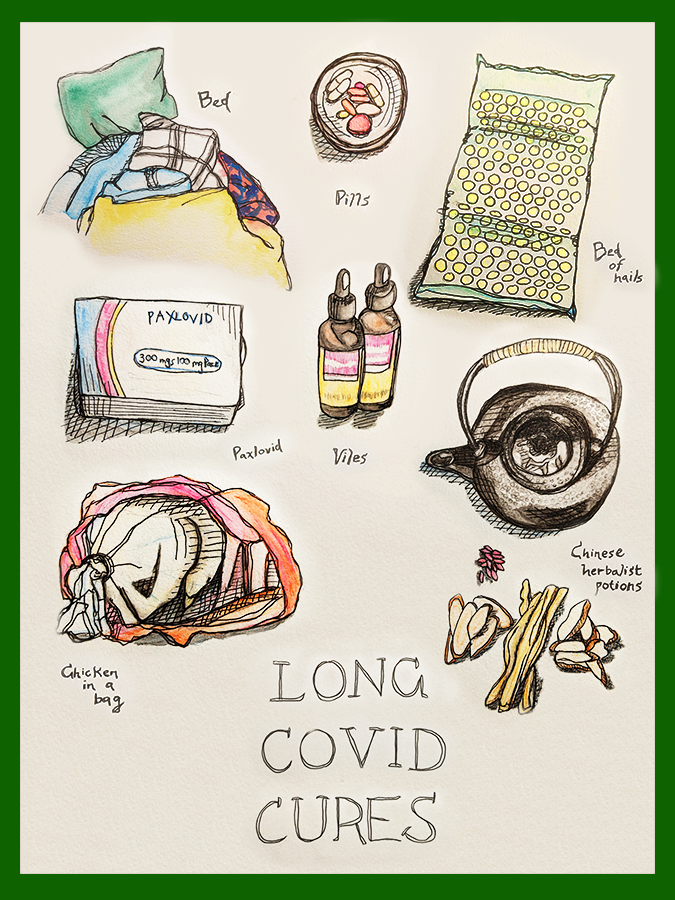

On clinicaltrials.org, a number of studies purported to test the effects of Paxlovid on those with long Covid. Kaiser will give you Paxlovid if you are currently testing positive for Covid, but not otherwise. Lying to Kaiser for Paxlovid remains an option, but in the meantime my backchannel supporters have collectively prescribed me sleep, moderate exercise, “pacing”, Tim Burton’s _Wednesday_, ashghawanda, ginger, turmeric, tulsi, probiotics, Pu Ji Xiao Du Yin tablets, Vitamin D, meditation, acupuncture, acupressure mat (“bed of nails”), Remdesivir, CBD, and the nuclear antiviral potion 党参, 北芪, 白术 , and 杞子 (“put them on the phone with me if they say they don’t have it”), boiled with a whole chicken .

What’s troubling about sickness is not only pain and discomfort, but the company it keeps with deterioration and fear. While I’m learning to manage my symptoms with some help from my friends, it’s their persistence itself that is acutely distressing. I’ll stand decrepitude for a discrete span, but if it goes on? The creeping fear that my best days are behind me, that I’ll never again play a 90-minute soccer game, go out dancing, or engage my students with the full force of my personality—these thoughts intrude, and it takes an effort to return to more rational equanimity, which says I’ll get better with time and patience, as I most likely will. It’s in these panicked moments that I want the whole thing to be over immediately.

—

And yet.

::a little more::|| “an elf witch of terrible power… all who look upon her fall under her spell and are never seen again” “you bring great evil here ring bearer”

It’s winter here in Oakland, and has been raining, dark and cold, which adds to the overall gloom and does not improve my symptoms, but suits me. In the evenings, when I’ve exhausted my potential at school, I can yearn toward bed, and time alone, without FOMO or regret. In these moments, I’ve thrilled with excitement at the cover my sickness affords me to _hide_, unsupervised and out of view. Alone in my room, I’ve hung a projector sheet taut between my walls and pushed play on some movies I’d been too unfocused to watch in normal health—some great, like _The Worst Person in the World_ and _Decision To Leave_, others merely good. Each felt like a milestone of attention, and the projector-from-bed situation has a classic, moony appeal. I’ve turned on NTS Radio’s _Poolside_ mix [link] and combed my back-catalogue of cellphone photography on Google Photos, opening batches to shine in Photoshop. With these, I started this Tumblr, the images a buffer of creative content softening my self-criticism about writing and making it, strangely, easier to write. I’ve sat in the middle of my room with my thick white headphones on my ears and my electric guitar slung across my lap, playing droning, soothing power chords. When I’ve been too tired for any of this, I’ve watched Premier League soccer, which though emotional [link], has no real mental cost on a per-game level. I nap through whole games and awake with drool on my pillow, deeply relaxed.

After they travel through the Misty Mountains and lose Gandalf to a Balrog in the Mines of Mordor, the Fellowship of the Ring spends a long weekend in Lothlórien, the leafy Elvin hideout where time slows down, and the saga of the ring, though ongoing, takes a pause for sleep, laundry, rehabilitation and resupply. The place is a hidden resistance center against the rush of Sauron’s advancing darkness. Even at my most self-aggrandizing, my about-town quests and schoolroom labors are less charged than Frodos. But I think of him in Lothlórien, swaddled in that soft white bed, as I recuperate in the quiet safety of my own sickroom, a strangely beautiful, sheltered space outside of time that, were it not for the painful fatigue, I’ll be sad to leave, and, in certain will look forward to visiting again, should I recover as I expect to do. For the poor soul under pressure—you and me and all of us—to disappear is alluring; when life swings a cloak or moment of invisibility over you, when you can slide beneath the boil and swell of things, a little bit of hiding can be one of life’s great pleasures.

—

One problem with the state of being somewhere on a mountain above survival and below self-actualization is that you are forever asking yourself, “Is this what the path to self-actualization looks like?” as you are doing all manner of things that one would not think lie along the path to self-actualization. “Am I self-actualizing?” I ask myself as I watch a fourth episode of _The Mandalorian_, eating popcorn for dinner in bed. “Is this what self-actualization looks like?” I pause to wonder as I click on the third, fourth, fifth pages of sale socks on ASOS.

Purpose Peak: it’s _the_ peak. From its apex, I’ll cast my leaden ring into the heaving cauldron, assured and exalted forever. But until then, beneath its fiery eye, there is no uncounted moment, and its long shadow is cold with confusion, self-disappointment, and anxiety.

++”What a man _can_ be, he _must_ be.” (Maslow, 13)++It’s a heavy narrative, and like most people, I’ve lived beneath it, alone, for most of my adult life. Self-actualization is inherently personal. Everyone has their own lifework to discover and fulfill according with their proclivities, hangups, dreams, philosophies, opportunities, and formative early wrongs. ::These are types.:: Some are hedonists, detesting toil, for whom life is a bottomless bucket to fill with as much pleasure and experience as possible. Others are freedomists, fearing constraint. Power hoarders are never to be humiliated, and hoarder hoarders stack against want. And so forth.

By nature I am, and have always been, a contributor, specializing in generative public projects. It has been the purpose of my life, as I felt it, to express my potential energy and facilities into interesting, unique, and useful forms for others—big parties, scrappy small businesses, high school arts programs, backpacking trips, world-swallowing explanatory writing. I was an exuberant, talented and well-loved child in the age of unconditional acclaim, and I’ve retained the compulsive maximalism of one whose sense of self-worth, and most reliable source of conditional love, comes from pulling things off for a crowd. Gradually the pure delight of performing as Michael Jackson for a cribside crowd of stuffed animals became the insecure attention-seeking of adolescent positioning—even if that was never my _only_ motive, and no matter how big-hearted the project. I’ve built wonderful community through my efforts, but contribution has always been my freight to carry up the mountain, and until my mid-thirties I truthfully could not conceptualize my life in another manner. By what measure other than social contribution could one possibly value his life? For what else could one merit love, justify and tell the story his existence here?

The eye of this totalizing mandate never blinks, and beneath it, fatigue takes on the intrinsically negative value of something spent: an empty battery, a snarled power line. For me, being tired has always been the most vexing state, because it interrupts the sense of self I’ve built around activity. To be sleepy or lazy before conquering the day’s possibilities was to mildly underperform existentially. So, though overused, I would never allow myself to rest. I considered every waking hour an opportunity to have, at least, an expansive moment. Empathy and exposure are some of the tools of the trade for contributors, and I maintain a practically inexhaustible list of movies, series, books, magazine articles, world language courses, audiobooks, and meditations to consume, which in in my value system supersede mere entertainment. Yet edifying is rarely also brainless. No matter how may hours I spent fruitlessly drooling over Rotten Tomatoes without pushing play on anything, it wasn’t obvious to me that concentration is antithetical to recharge. I’d fall asleep on one hundred tabs, incapable of narrative detachment, waking again tomorrow under the same decree.

Somewhere [link] I read a theory about why humans sleep at night, instead of in the daytime—and why our eyes are consequently tuned for daylight hours—which had to do with lions. On the Serengeti, the hunting hours had to be split between apex predators. The lions, most supreme, went for the prime nighttime hours, and early man adapted to hunt when the lions were sleeping, in the heat of the day. I don’t know whether this is true or not, and find no easy reference on the Internet, but I like imagining that the daylight preference of our species is down to our long ago starlight negotiations with the ancient prides. In the same book, I read that early man would spend enthralling days hunting or gathering, but spent most of their time in camp doing chores, telling stories, and just kind of playing around. That way of living seems chill. Healthy.

With the advent of agriculture [Sapiens link], our forebears took up the grinding millwheel of species expansion: grain, cattle, and human alike. Up with the sun. For all the romance and smell of plowed earth, that mode seems less chill. Poor, brutish and short. But boy: _still simple_. I imagine the problem of existence was cleaner during those long eons. It had to have been: the scope and field of action for most everyone were given and confined, community and spiritual practice inherited. There were only so many ways one could imagine being. Survival, luck, and mystery: with great difference of presentation across the globe this manner of being human continued for the near-entirety of the human ::wave upon whose crest we are the effervescent froth.:: ::mixed metaphor::

After the colonial upheavals, capitalist expansions, industrialization, modern science, and the Internet (to name a few), much of the endowment one built one’s life and slept on— the family home and trade, its religion and culture, its heirlooms, wedding rings, photos, cousins, language, mule, words for love, recipes, congenital limitations, ancient hatreds, cosmologies, jokes, and identity — is forgotten, castaway, dislocated, disseminated, dumped, taken to the grave, or otherwise floating in the gyre. As a metaphor, the mountain of security and self-actualization is haunting because we not only need to see and climb it, we need to strap it together ourselves from this oceanic current of parts. For the shipwrecked, treading and jostling, absolute self-creation is a necessity disguised as an opportunity. Certainly it’s both. It’s invigorating, liberating, dazzling, isolating, poorly-understood and utterly exhausting. “It’s a lot,” is on everyone’s tongue this year. No wonder the Will to Hide.

—

The first time I can remember experiencing the seductive magnetism of hiding out was when I started taking long drives across the country in my Honda Accord, during the breaks between college semesters. ++Picture++ The longer I was alone, the more the hermetic privacy of the car overtook me, and I would succumb to a skittish shyness of people and decisions completely counter to my normal personality. I would drive into a place—some Cedar City, some Mt. Vernon—and nearly fear talking to the strangers there. I’d freeze with panic picking a place to eat, preferring instead the anonymity of my solitary, ::unnegotiated:: world. I recorded myself talking into a battery-powered tape recorder, or humming aimlessly as I slapped the dashboard with my thumbs. I listened to the _Harry Potter_ audiotapes narrated by Jim Dale. It was intoxicating to be unreachable, untethered, on the loose in the beautiful world, but there was something of protest in it too, a kind of proto-burnout from the kinetic motion of high school and liberal arts college, though I couldn’t put my finger on that yet.

I think about those trips like a dream world to which I never returned. I over-stuffed the years after them with all manner of hustle and movement, people and projects, living life at a ceaseless full bore, so much that when I search my memory for extended moments of hideout post-graduation, I find exactly none until the pandemic shutdowns of 2020 and 2021.

To the extent the shutdowns were pleasurable, it was as a mass-hideout event. Unpaid and less inhibited than their teachers, my teenage students on Zoom hid their faces behind their black boxes for a year and a half. It became our forced bargain that if I would allow them to hide—and my remonstrations were powerless to make them appear—they would allow me to hide from my job as well. No amount of work I put into my lessons and outreach made a dent in engagement, and eventually we settled into not so much a course schedule as a hangout routine. My evening virtual film screenings drew better attendance than my classes, even if the visible faces remained few.

Like my students, everyone I knew was hiding during that time, each according to their abilities, resources, and responsibilities. After the initial frenzy of that first spring and summer, when I worked at the food bank in the mornings, anxiously baked sourdough and tried to get my students online, my world unmoored into a loose, languorous drift where nothing much was possible, and nothing much expected. Most of the time, I hid out, overcome for the first time since those car rides with the delirious pleasure of privacy and peaceful silence. I took long walks and listened to books on tape or birds singing, breathing the clean air of the depopulated Bay Area. I started playing _Civilization VI_ on my OUSD MacBook through the evening. I liked the opening phases of the game, when you navigate your tribe through the outer dark, discovering the nature of the world you’ve awoken in, clutching your spear. I read a lot of books, spent long weeknights with friends, and ate a lot of pasta. It was a separate peace.

I wasn’t completely detached, of course. The protest that I now know accompanies and motivates all hideouts was overt and pronounced during the pandemic. People were dying and hospitals were filling up. Trump was president. I anxiously read all the news. When the George Floyd demonstrations came down, I took to the project of antiracism, reading all the books I could and preaching that gospel to my white friends with the radicalism of the newly evangelized. Change felt possible.

There was other dissent as well. A breach opened in the social contract under which you strive for a lifestyle and self-actualization through work. Guerrilla hideout movements—quiet quitting, hikikomori, lie flat, and college disenrollment among others—began or deepened. Many of those who could afford to hide in bedrooms settled for full-time hideout until something more than a paycheck and drudgery could be found at work, free-rider problem be damned. Facebook read the tea leaves (incorrectly, let’s hope) and became Meta, a co-opted corporate space to hide from the world. All of these movements continue.

As we returned to the classroom last year, I was happy to be back teaching in person. The job had become a grey doldrum, devoid of the human contact that makes teaching pleasurable, and like everyone I was ready to be done with Zoom. At the same time, I had little desire to do all the things I used to do. Our mantra as we returned to the building was, “Can we not?” I tightened my boundaries, and started going home right after the last bell, but teaching is a taxing profession, and there is no way to keep it in a box. By now, my hideout spaces had once again mostly disappeared until this sickness gave me the pretense to take some time aside.

—

The special dispensation singular to teachers in working America is the academic calendar and its holy season, summer. Each summer provides a new opportunity to breathe again, after a year submersed.

Last summer, after the final bell, I blocked off an entire month to be at home without plans. I had recently discovered the practice of **“Plays, Not Plans”** in the classroom after realizing that the stress I was feeling there was equal to the amount of effort I spent scripting lessons, heavily investing in specific outcomes. Classroom spaces are microcosms of the outer world. Energetic and emotional, for the most part they can’t be made to follow precisely predetermined steps, only guided in favorable directions. Plays are planned flexibility. Instead of measuring my success by the number of students who followed a written plan, I was happy if I had a few plays for every classroom situation, big or small, and if those plays resulted in some kind of constructive outcome. For an accelerated learner, I’d have a few challenges to keep her engaged. For a chronically absent student, I could make a phone call home, or work with the soccer team to make an attendance contract, or meet during lunch if he showed up at 11am, often after working until 6am. If we could have a positive conversation about choices and balance, then I succeeded today as an educator. Keep your expectations kind, and your outlook will follow, was my general idea, and it was transformative for me in the classroom.

I thought it might be nice to apply this concept to my own days during a summer break as well. I wrote down a list of few plays to try without pressure, off-calendar and off-alarm clock. I set the time aside, drank a blended cocktail on my stoop, and awaited a lightning round.

What happened instead was, at least for a while, I moped: for two weeks or more I could not get up the force to do any of the things I’d been excited to do. Even my bedside book stack and my “Watchlist” was too challenging. I scrolled Instagram, home repair Youtube, and the seedier streaming neighborhoods. I thought it was malaise, fatigue or drift, and I found it distressing. I could feel the time I’d set aside for my plays wasting away unadorned with memorable moments or victories. Sticky fatigue was especially distressing when it came in summer, at the cost of more glamorous pursuits. No one wants a bedroom summer. I could have gone to Italy!

Eventually, after a week or more, I began to snap out of it. The amplification of the school year that had been electrifying my system had run its course and, thus emptied, the wires were quiet. As the days went by, I started to feel more and more relaxed, and, critically, **_unrushed_**: positively good in a way that I had not felt before in my adult life. I read a magazine, called a long lost correspondent, drove to the beach, made a smoothie, walked to a friend’s house, drew a landscape in crayon, and looked at the city from my roof, drinking cold sake as BART went by before the sun. In moments like these, the emerald bottomlands, the amber waves of grain between the mopey comedowns and the nervy upswing before the return to school, I could feel the pressure I was under by its lack. My ears practically popped. Someone turned up the vibrance. The ::electrification:: increased as time went on. After a few weeks, simply because I **_wanted_** to, I’d finished some books, drove to the beach twice a week, meditated most days, started running again, planted a small garden. And, without the destabilizing, insistent whisper of other enticements or goals, I was finally able to do some writing I was proud of. It was a super power: the ability to want what I wanted to want, and to do what I wanted. **“\_Dolce far niete\_,”** is an expression that my roommate tells me they say in Italy. Sweetly doing nothing. I wasn’t doing nothing, but I was doing it sweetly. It was a sweet spot.

This state lasted until about a week before the start of the school year, when I again began to feel overswept with preparations and commitments: normal life returning, as it must. I didn’t delude myself that I could keep a summery flow alive throughout the school year, but it didn’t matter. I’d deeply cleaned house. My world was noticeably brighter. With a little spray and dusting, I could keep it within reach of that state. And the process was repeatable, down-scalable. Not only could I do it every summer, I could do a mini one on the weekend, chilling out on a Friday evening, passing Saturday sweetly, and ramping back up slowly on Sunday, without compulsively scheduling every moment; without too much personal disappointment when I felt tired and needed to mope. I started celebrating “Noplansuary” after the rush of the holidays. I blocked off whole weekends. I said maybe to a lot of invitations. I started taking my sweet time.

—

(to be cont’d)